Emily VanDerWerff is one of the foremost reasons I do what I do.

A longtime pop culture critic, Emily VanDerWerff was one of the founders of The AV Club‘s TV Club, and was many peoples’ introduction to how popular media can be treated with the same regard and respect as “high art.” Now, VanDerWerff is the Critic at Large for Vox.

While VanDerWerff’s introduction to the podcast scene was an early conversation podcast called TV on the Internet, she’s been more recently involved with Arden, a true crime parody audio drama and modernization of Romeo and Juliet, and Primetime, Vox‘s podcast about how TV affects society.

I have always been inspired by VanDerWerff’s work, and now, I’m also inspired by VanDerWerff’s life. On June 3rd, 2019, VanDerWerff publicly came out as a trans woman in a beautiful piece for Vox. She and I sat down about a month earlier to discuss the process of coming out, talking up underdog media, and how her identity will be reflected in the writing of Arden‘s second season–a conversation that helped my coming out as nonbinary. As she writes in “The Catastrophist, or: On Coming Out as Trans at 37”:

What I believed for too long, and what you might believe too, is that your body is not a gift but an obligation. That it is not who you are but a series of tasks assigned to you by the accident of your birth. This is not true. The best obligations — the only real obligations — are chosen. Your life is your life. It is worth fighting for.

This interview has been edited for conciseness and clarity. Tis interview contains spoilers for Arden‘s first season.

I want to get into your history before you started writing, because you seem to never talk about it. Your official bio on Vox reads (as of this interview), “[Emily] Todd VanDerWerff is the Critic at Large for Vox. Before that, [she] was the TV Editor for The A.V. Club. Before that, [she] worked at a bunch of newspapers. And before that, the Internet wasn’t around, so who cares?”

When I was at The AV Club–and this dovetails with the transness of it all–I over-shared a lot. There were a couple of arenas I felt were off limits: one was my marriage (I had to get my wife’s permission if I was going to share a story about our marriage), and the other thing I didn’t talk about was a giant thing in the corner of my brain marked “YOUR GENDER” that I just didn’t try looking at. I was radically open and honest about everything else. Especially at the end of my time at The AV Club, there was kind of a turn against that sort of writing. Even when I was at The AV Club, I felt like I over-relied on saying, “This hit on this personal button for me, and that’s why I liked it,” so I was already pulling back from it.

When I got to Vox, I think I might have over-corrected in the other direction. At Vox, I was starting to deal with a lot of this stuff I hadn’t been thinking about, and it was hard to write about myself without getting into that.

I think I was talking about myself without really talking about myself.

Did you have a focus in journalism in college?

Just print. I wanted to be a great writer, and I think what frustrated me about journalism, at least at school, was that I didn’t want to be a great reporter. I didn’t really want to be a great journalist. I wanted to be a great writer.

I think I’ve backed my way into being a decent reporter and a decent journalist, because I loved writing so much, and this was a way to get paid writing, so I may as well teach myself these other skills. But my passion was always the words, putting them together. There was one piece I wrote [in my college newspaper] about hunting season, which was a big deal in South Dakota, that was really wrestling with my own masculinity. At that time, I had no clue, but I wrote about how I never felt like I fit in. It was supposed to be a reported essay where I went out with some hunters.

I had always wanted to write about movies and TV or for movies and TV, and when I moved out to LA, I had that in mind. Focusing on TV criticism was just a lucky accident of timing–being in the right place at the right time to get in on the first floor of the recap era and ride that elevator as high as I could go.

One thing I’ve always loved about your criticism is that you often choose media that’s hard to defend in the public eye. In a 2015 AMA on Reddit, you said that one of your biggest influences in your criticism was Toy Story.

Why do you think it is that you tend to focus on these unsung heroes and try to get people to see them in a different light?

Obviously I work in an industry where we’re all worried about traffic, and I know that if I write a Game of Thrones piece, that’s going to take care of my traffic for the week. So why not spend my time on other stuff, the stuff that I feel most passionate about? I’ve discovered what I feel most passionate about is the stuff that has these weird niggling little flaws that other people fixate on, but I think, “No, those are what make it great.”

I loved the movie Black Swan back in the day, and I couldn’t quite articulate why. I read a conversation between Matt Zoller Seitz and Andrew O’Hehir at Salon talking about that movie, and they discussed that the flaws make it stronger. The flaws are so obvious and on the surface, but because it has them right there, it sort of . . . eats them for breakfast, and becomes a stronger movie for it. That really defines a lot of what I do.

A lot of people like the show Parks and Recreation, and I love the show Parks and Recreation, but that’s every much a show that holds you by the hand and says, “These people are good. You’re good. This is a fun time, and a fun place to hang out.” And then I look by a a show by the same guy, Mike Schur, The Good Place. The Good Place does not do that–it’s a show that’s constantly trying to run out of room, and it’s going to run into a wall someday. I’m always drawn to that, because I’m more interested in something big and ambitious that we don’t really have the capital for, but we’re going to trust the audience to get there with us.

I’m always going to forgive someone who over-shoots rather than someone who just takes dead aim and hits the target. That is pretty different from a lot of other critics, who are much more interested in people who are in complete command of what they’re trying to do. I’d rather look at someone who’s going to fall on their face at some point.

Does this transfer at all to your work in Arden?

I think that people will see this come through in Arden and some of the other dramatic writing I’ve done. I do think about this, still first and foremost, as someone who likes to tell stories. I understand that every story is inevitably going to have periods where you’re not sure what’s happening, where it’s going. I think we are in an era of wanting to see entertainment that takes us by the hand moment by moment and tell us how to feel. The tone is always carefully handled.

A RadioPublic embed of the trailer for Arden, which can also be found here

We wanted to do something much bigger than we necessarily know how to make. There were times in season one where we totally bumped up against the limits of our ambition, and we learned a lot from those. We had the idea itself of doing a fake true crime podcast that would stay within the framework of a true crime podcast, but with two dueling voices in the space. In episode four, we came up against the idea that we couldn’t do that across the whole season. We pivoted to make it more of an ensemble piece, which I think is why the show works.

It was unsustainable, because at a certain point, you realize that the writers were guiding you, and you rebel against pretending it’s real. The deeper we get into season two, the less we are a “true crime podcast.” Season two is Hamlet, and we are doing an episode that is a very overt Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead episode, and in no way would that ever be done in a true crime podcast. We have a reason–you could argue, “Okay, they were being recorded the whole time.” It’s the thinnest possible gossamer veneer of keeping the premise of the show sustainable.

The further we get into it, the more we just want to do stuff that scares us a little bit. Eventually, we’re going to run out of room, and we’re going to badly fall on our faces. One thing that I think has really saved us in season two is that we’ve brought in a writer’s room. We have a full gamut of people telling us an idea is terrible, and the scripts we’ve gotten so far are super strong. I’m really excited for people to hear how the show happens.

I want to pull back a little and get the chronology and get into how you go into podcasting. I know you had TV on the Internet, which it looks like is archived?

TV on the Internet is . . . off the internet. My writing partner and wife, Libby, co-wrote episode eleven with me, and is co-writing an episode of Arden season two with me. We also have a pilot that’s floating out there. When we started this podcast, we said stuff we probably shouldn’t, because we said it when we were dumb kids. I learned a lot about audio from it: the audio was terrible, but it got better across the show. We have it all somewhere if we really wanted to revive it, but some of those episodes sound abysmal.

TV on the Internet, it was 2009 and I was listening to a lot of podcasts I enjoyed–that was the era of getting friends together and just talking about stuff. I didn’t really see one about TV. There were a couple, but there weren’t any I was super into. Libby and I said, “Let’s just do it.” Our publishing schedule was wildly erratic. We were all over the place. We never quite found the format. There was fun stuff in there–people will still quote bits from the show to me.

Libby and I want to do another podcast together, but we want to do something more rigidly formatted, so every week doesn’t become a two-hour ordeal of me driving her crazy. One of the things that we accidentally learned on that show is that we opened every episode of the show with a comedic bit, and then we’d cut to the theme song. Those often became our favorite parts of the show. The ostensible reason for the show, television, eventually fell by the wayside–because what people were responding to was the two of us hanging out, or the various guests we brought in.

Tell me about Primetime.

When I pitched Primetime, it was You Must Remember This meets television. I thought I’d just sit there and tell a story for an hour. I had to be pushed to let in interview subjects, and now the episodes are not just an hour of me rambling. They’re pretty tight 20-25 minutes, and I’ve really been impressed with it. Obviously the people at Vox on our podcasting team are tremendous professionals, and I’ve been so excited to get into this show.

The first season is six episodes: four episodes are about fictional depictions of the presidency and how they influenced our own thoughts, and then we have two episodes on how presidents have used television. Actually, our fourth episode is on Murphy Brown vs. Dan Quayle, a pivot episode because it’s about both things at the same time. One of the things I learned while doing this is that the Murphy Brown vs. Dan Quayle case was steeped in race in a way that I hadn’t even considered. The whole thing was a racist dog whistle, and because it was about a white TV character, most people didn’t pick up on it. Doing our research on it was so fascinating.

A RadioPublic embed of the episode, which can also be found here

What was the first audio drama you ever heard?

I’ve listened to BBC-type stuff all through my life, but if we’re talking about this modern podcast era, the one I always come back to is Limetown. That directly is the one that inspired Arden. Listening to that, I knew it wasn’t real, but I wanted it to be real. Arden got away from that very quickly, but listening to that really inspired me in terms of how you could present a situation that had verisimilitude while still allowing the audience room to know it was a fiction. The release of knowing it’s fiction allows you to more fully engage with it. I like the tension between reality and fiction that exists in a lot of audio dramas.

You wrote some of Arden season 1 before you were out to yourself as trans, and some of it after. What was the process like? Did writing in that space contribute to that process at all?

Oh, my god, yes. It’s kind of a thing of Arden lore that Brenda was written as a man in the early pilot script. Tracey [Sayed] and Michelle [Agresti], when we heard them together, it was just amazing. It was instantly right. We actually had Tracy read Bea and Michelle read Brenda first, I think, and even then there was something there. Now that I’m starting to say this, it feels like an obvious answer, but we took this character who was brimming with masculine energy, and we wondered how far we’d have to push the character to make them a woman, and the answer turned out to be not very far. We obviously changed a couple things because she’s now a female police officer in a small town, and there’s prejudices within that; she’s a lesbian police officer in a small town, and there’s prejudices within that.

I came out to myself in March 2018. I vividly remember in January 2018, we had this meeting for writing the second half of the season. Sara [Ghaleb, co-creator/writer/producer] said, “If we’re going to tease the idea of a will-they-won’t-they between Bea and Brenda, there has to be some element of sexual frisson.” Some part of my brain said, “Do you know how to write a lesbian relationship?” and then another part of my brain that was kept behind a locked door said, “Oh yeah. You do.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about not the period after coming out, but the period leading into coming out–roughly from summer of 2016 to spring of 2018, about 18 months. I mark the beginning as when I started working on this pilot that my wife and I are in the process of selling, which was about a teenage girl. It was so easy for me to write her in a way that it never was to write men. I had always questioned my gender, but I didn’t want to talk about it, I didn’t want to admit it to myself. Writing that script made the questioning go away in a way that kind of head-faked me. I thought that maybe I wasn’t trans, and maybe I just needed to write more female characters. But then, when the script was done, the dysphoria came back twenty times more.

That was the era in which I was writing a lot of Arden. Suddenly I was writing a show that was originally going to be a very straight Moonlighting riff, and suddenly it becomes a Moonlighting riff with two women. Bea is probably one of the more autobiographical characters I’ve ever written, which is really kind of a self-own, because Bea’s so ridiculous. I wrote a lot of the Bea lines in our season two premier, and I find her lines so easy to write. I immediately slip into who this woman is, her pretensions, the ways she tries to save face when people think she’s being dumb.

The other big thing that happened was that we started conceiving of the full arc of the season, and we always knew that Julie and Ralph were alive somewhere together. The idea was going to be that Julie’s parents were trying to pressure her to get an abortion, and she ran away. I don’t remember where that idea came from, but we’re doing the season in Fall 2017, and we felt like we needed a stronger reason for Julie to completely blow up her life. We wanted it to be that her parents were total assholes, but that she had proof positive of that. We didn’t want it to be just one thing. We wanted it to be many things that culminated in her parents being the biggest jerks alive.

Fall 2017, of course, is the era of #MeToo. We were telling a story about a young woman in Hollywood who has something traumatic happen to her, and she runs away. At the time, I sold it to myself as a way to go from Point A to Point B that makes sense and resonates with the culture, and is something the three of us feel very strongly about. But I also felt like I needed to weigh in on this, that this was my conversation to be having.

That was in that era of starting to understand myself as a woman, not as a man–I was allowing myself to understand myself that way. I had always known, I just . . . I needed to give myself permission, and the writing projects, the pilot and Arden, were this weird way of tricking myself into thinking about these things that I needed to think about. Then, when I wrote Julie’s monologue, and Libby and I wrote 11, and that stuff was written right on the cusp of coming out or right after coming out.

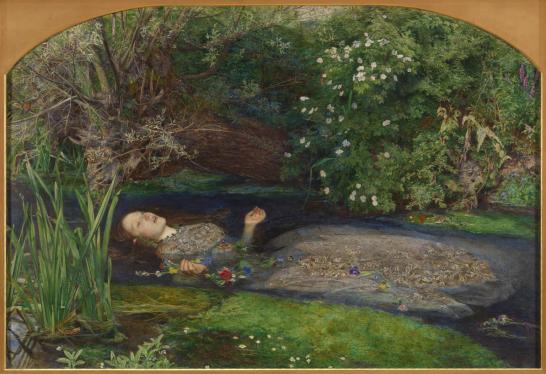

In season two of Arden, you’ve said that Ophelia (Olivia, in the podcast) will be a trans woman. I don’t want to get into spoilers, but I do want to know about the thinking there, especially given the landscape of trans representation.

I will say, without spoiling anything about season two, but I’m very excited to dig into who she is. I will say that we let Romeo and Juliet live, so we are not above changing the Shakespeare canon if we want to. I do think that you can’t do Hamlet and not have some sort of tragic death. It is inherent to that story.

It’s sort of the death-iest Shakespeare.

Yeah, outside of Macbeth–but Macbeth is campy death, you know? And Hamlet is very sad, somber, tragic death, and everybody is just not dealing with their shit. And that’s kind of an interesting thing that we’ve already realized: when you’re writing Hamlet, you’re writing a ton of people who aren’t dealing with their shit. If you make Ophelia trans, she, by definition, has already dealt with some of her shit. That shifts who that character is.

Olivia enters our story as being an example of a person who dealt with her stuff. We think about the characters a lot as mirrors of our five main characters, and Olivia brings out really interesting colors in all of our five main characters. Obviously, I’m not going to tell you if we’re going to repeat what happens to Ophelia in the play, but at the same time, I think you have to have room to tell dark and tragic stories about queer people.

Not every story about queer people should be dark and tragic, but our two leads on Arden, both of whom are going to survive for the entirety of the series–I assure you–they’re both queer women. We have other characters within the show who are asexual, who are figuring out their sexuality. We have this gamut of characters within LGBTQIA spheres. I don’t think every story we tell about queer people should be a bad story, but queer people have a right to bad stories too. I feel that very strongly, as a baby trans. We have a right to sadness, and anger, and hopelessness, too–and nuance.

We have a trans Ophelia, and the only thing people know about Ophelia is that she dies. Are we automatically going to get dinged for that? Maybe we will. If you are listening to Arden for positive queer representation, I would hope it’s still there. Bea and Brenda are messes, but they’re fun messes. I get it, but to me, there’s so much more to stories where there is allowed to be nuance, and despair, and hopelessness, and rage, because that’s closer to life.

Since coming out, I’ve lost people who were super close to me. I’ve had relationships completely shifted. I “was” a white straight guy in America, and I’m “gonna be” a white woman. Statistically, I’m the second worst. But still, there’s so much to that. I am losing something in the pursuit of being myself. I absolutely get the need for positive representation.

The sanitation of queer stories has always felt like another form of dehumanization to me, and it’s never felt authentic to me. I feel like the insistence on only telling the positive stories, especially if it’s coming from a writer who shares the marginalized identity of the character, is false and confusing.

As we’re talking about it, I’m getting very emotional. I apparently believe in this deeply. I want to hear the story of my marriage, where I came out as a woman and my wife took 36 hours to get to the place where she was okay with it.

But I also want to hear her side of that story, where she was a successful, comfortable, straight-passing bisexual woman in a straight-passing relationship. Suddenly, now, she’s no longer in a straight-passing relationship through nothing she did other than continuing to be here. There’s a lot of complication there that gets lost if all we’re telling is the story of how our marriage survived. It did. It survived. It’s stronger than ever. We’re happier than ever. If I’m just telling you, “Yes, you can come out as a trans woman and stay in your marriage and preserve so many of your friendships,” that is true, that is absolutely true, but that leaves out a whole side of that story from someone who has had her own feelings, has had her own situations to deal with. And I think that story is also fundamentally happy. My wife would not be here if she was not still in love with me. Not allowing her story to be a part of the story is just as dehumanizing as the idea that I could be played by Jared Leto.

What podcasts are you listening to right now?

I’ve been making my way through Our Opinions Are Correct. This is Annalee Newitz and Charlie Jane Anders, and Charlie Jane Anders is one of my trans writer idols. She is a novelist, a journalist, a critic. She’s written for television, and I’m just continually blown away by everything she’s done. [The podcast] is a discussion show where they talk about a topic in science fiction each week. They pull it apart from all different angles. My favorite episode so far was about how hard it is to imagine how an alien might think, because you’re inevitably limited by your own human capacity. They have really great chemistry. It’s not as funny a show–it’s a little more science-minded, as they’re both science writers and science fiction writers. I’ve gotten so many great book recommendations from that, and I’m really enjoying it.

The audio drama I’m listening to is Unwell. I had not thought about sound design at all. Arden is a show where that is very forgiving, because Arden is a show produced in a radio station, and we know how that sounds. The main thing the sound design in Arden has to do is be unfussy. Unwell, kind of like What’s the Frequency and Greater Boston, has really made me think about how to tell a story using sound. Without even thinking about the writing, what are the technical properties of how you can tell stories using sound? When I think about telling a story using images, that’s a fun thing to think about, because we think about audio drama as a medium that’s very dialogue-friendly and dialogue-heavy–but maybe there are ways to do a “silent audio drama,” if you will. Obviously not silent, but a dialogue-free one. When I listen to Unwell, I can see how this would work.

You can find Emily VanDerWerff writing on Vox, and you can follow her on Twitter.

Listen to Arden: Apple | Google | PocketCasts | RadioPublic | Website | RSS

Listen to Primetime: Apple | Google | Spotify | PocketCasts | RadioPublic | Website | RSS

Leave a comment