The Mermaid Palace team talks tactics for bearing your heart and keeping it safe

It’s both fact and cliche that podcasting is an intimate medium. This concept is something audio veteran Kaitlin Prest has spoken about for years: “I’m a straddle millennial. I worked in the age of actual broadcast radio. And in those days, when we were speaking out on the air, we were talking to thousands of people at once. [With podcasting,] we’re really talking to one person in their ear, and it changed how close we were able to become with the listener.”

But when it comes to intimacy in audio, Prest’s work has always taken the concept to new depths. Beginning with her podcast Audio Smut in 2008, Prest has aimed to tackle the most pressing, personal, pervasive questions around love, sex, and relationships. In 2014, Prest began The Heart, a PRX podcast that would go on to win several awards and be featured as a Peabody finalist.

In 2020, Prest has gone from making her own work about intimacy to starting an audio art company, Mermaid Palace, with a slate of new colleagues and collaborators–including the new producers of The Heart, Phoebe Unter and Nicole Kelly, and the writer and star of fiction podcast Asking for It, Drew Denny.

The Mermaid Palace team are the foremost experts on intimacy in podcasting–so how do they bare their hearts, fears, and traumas to massive audiences? How do they keep themselves steady and safe? And what does intimacy even mean?

“As an artist, intimacy is inviting someone into a very particular part of my experience or interiority. For me, it’s often been about discomfort — being honest about myself and my own discomfort as a means of asking an audience to examine the ways they might contribute to that discomfort (when I’m talking about white supremacy, or gendered violence for example) or as an invitation to someone who shares my experience to look more closely at their own, to not look away from it,” says Kelly.

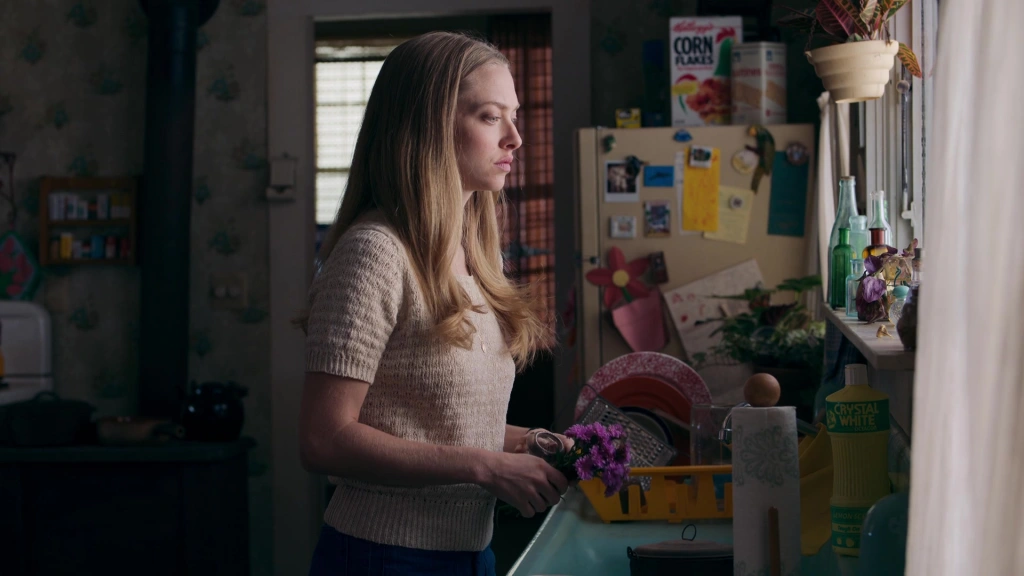

Denny explained, “Well, the first thing that comes to mind is physical intimacy, not just sex, but closeness, touch and tenderness. But for me, the far scarier meaning of the word intimacy is emotional intimacy, vulnerability, bare honesty, stark truth- in the presence of another person.” This is paralleled by a scene in Asking for It, when the protagonist, Goldie, explains that sharing her music is scarier than being naked in front of someone.

Denny shares the sentiment, but nonetheless included her own music with her band HIPS throughout Asking for It. “To me, storytelling and music go hand in hand. And as a filmmaker, film leans so heavily on music so much of the time. I actually took it for granted that our podcast would have an original score, and I took it for granted that we would have an original soundtrack because I’m a musician who’s used to having original scores. I’m a musician who makes songs, And I’m a filmmaker who has directed a composer on every single movie I’ve ever made because I always have an original score.”

To give listeners access to the story-heavy songs right alongside the episodes in which they appear, Mermaid Palace’s team at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation made a Spotify playlist that incorporates both episodes and songs. “Judy [Ziyi Gu] from CBC is our digital producer, and they are fabulous, and have made the combined playlist that mixes the episodes with the song [. . .] to help us communicate what the show is about to people.”

Prest’s somewhat self-deprecating answer hinges on one idea: trust. “The first thing that comes to mind is closeness, feeling invited in. I suppose it has something to do with a line that a lot of other people have, that I seem to lack, between what is considered public and what is considered private, and being on the other side of that line. Things that most people only share with the people they trust deeply and feeling on the inside of that line.”

Exposing the raw sides of yourself can be difficult, though, whether covering those topics as a documentary like The Heart or fictionalizing your own story, like Asking for It. It takes bravery, and in the words of Denny, it takes a resilience to rejection.

“You have to be aware that rejection is going to happen,” Denny says, “and develop a relationship with rejection that works for you. [You might be rejected] from an audience: getting panned by a critic, getting trolled by someone online, even getting threats from people, getting iced by someone who felt that they were somehow burned by what you made.” Rejection can sting especially hard when you’re making yourself and your story vulnerable.

Unter recommends interrogating your discomfort when telling your own stories. “It is difficult and terrifying! Sharon Mashihi is my editor on [an upcoming piece], and early in the process we listened to a draft and I was like, ‘Does this make me seem like a terrible person?’ She asked, ‘Why is that your question?’ She basically explained that listeners who would engage with the work on that level, like judging whether or not I’m a terrible person, would be missing the point, and do I really care that much about being liked?”

If you’ve found the courage to tell your story in a podcast, you’re halfway there. The next step is figuring out how to take care of yourself and your collaborators. Intimacy in creation means that you could be hitting some touchy subjects for yourself, your editor, your actors, etc. Prest explained that their team essentially has a house therapist, but that so much hinges on trust, communication, and self care. “Honestly, it’s been a journey for me as the person who’s asking people to do this type of work and promising them that it’s safe.”

Kelly’s advice is to pay attention to who’s in control in the creation process. ” We prefer our collaborators to feel as if they have control over the way they tell their story, or how they’re represented. […] Of course, I’m willing to push myself a lot further than I would ever push anyone else, and to write about certain experiences in Divesting From People Pleasing, I had to allow myself to sink into some memories, some moments of my life, that I generally prefer not to revisit. […] But I think it’s ultimately worth it to do. For ourselves as artists and for the listeners.”

So why bring vulnerability into your work? Unter’s simple reply cut to the core of the discussion: “Vulnerability is compelling. It’s compelling for the audience, but you might be surprised how compelled you are to tell your own story. Practice self care, put yourself in control of your narrative, and tell the stories you need to tell.”

This article is syndicated from a now-dead site that deleted almost all of the work of myself and my colleagues. Don’t sue me! Get bent! ❤

Leave a comment